“As bad as anything else”

Tout est Terrible

This entry is a translated loose transcription of a talk I gave at the Web a Quebec conference in April 2017 named "Tout est Terrible".

So, everything is terrible. That's a bit funny to say since so far in this conference, there's been a lot of talks about the amazing future and all the things new technology enables. All the new avenues and devices that should make our lives easier. People who know me are aware that I generally have a very cynical view of technology, and I'm personally scared of all these connected devices that obey my every word some other speakers are excited about.

Mostly, that's because the more time I code and spend in this industry, the more I know how things work behind the scenes, and the least trustworthy the whole thing appears to me. That's how I picked the picture for this slide, it's called "The Triumph of Death" by Pieter Bruegel and it's a bit how I feel about a connected home.

What I want to show is that we can have this very simple and basic application that looks very, very reasonable, and show a bunch of issues and potential bugs that can hide in it and surprise us in nasty ways, and that it's hard to really feel safe about any code out there. This is gonna be a spooky scary story!

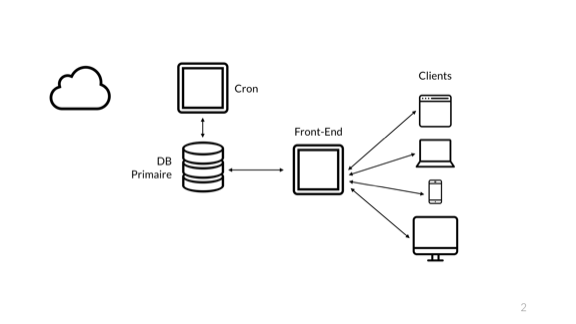

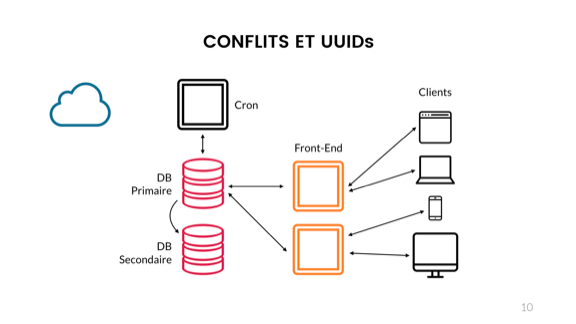

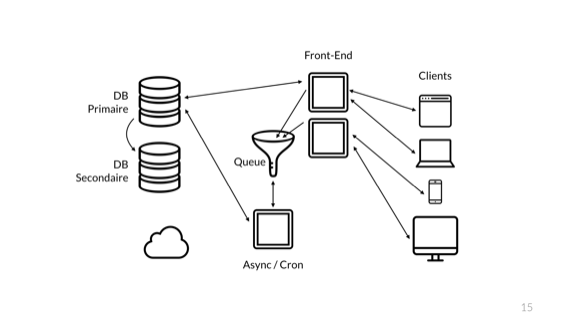

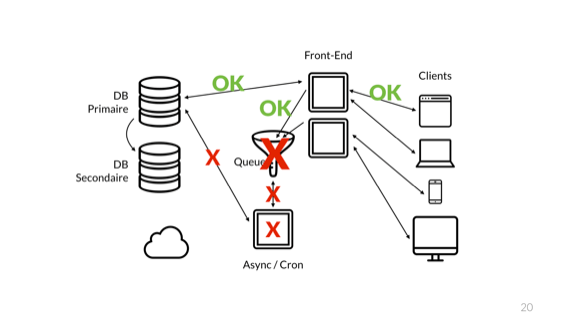

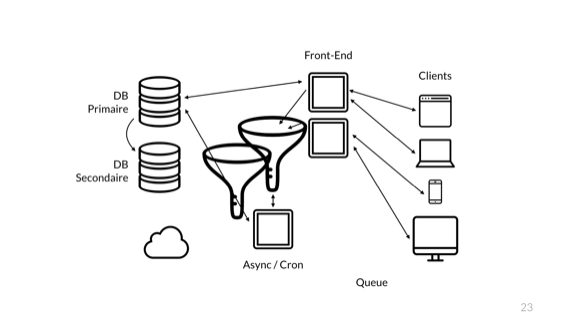

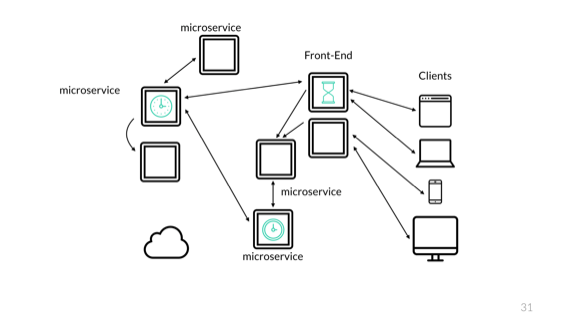

To show my point, I want to start with a basic application, one that mostly any developer in this room will have a fairly intuitive feeling for. Here I have my little web application. My users on the right have their own devices, that they use to connect to my front-end server, which runs some language that executes logic. That language connects to a database where it stores data. Then there's that cron job server used for some background tasks, maybe it's not used super hard. And then you have the cloud, which is likely used by a bunch of other stuff in the system. Maybe you store images in S3 or whatever.

So that's a reasonable app, but it's too easy to find problems in it: any machine goes down and things go bad. Instead, we'll look at this one:

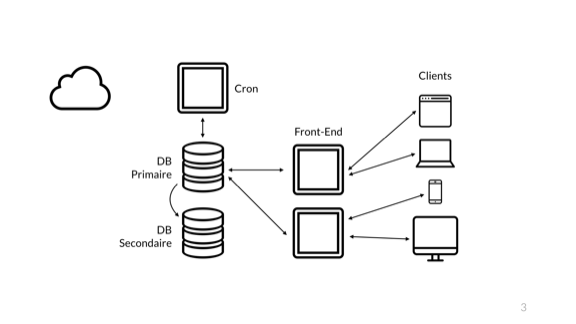

That's a safer one. I now have a redundant front-end, where I can deploy to one of them or have it break and still be accessible to our customers. The second database node gives us a hot-failover in case of problems, but it's not a back up solution. You just need one person to

DROP TABLE users;

with live replication to lose that hot standby so let's say we do the

reasonable thing and we have a back up in that cloud over there.Then there's still just one cron server because async tasks maybe are okay to replay just later. That's better. Our architecture is solid enough to get comfortable and start to worry about just the code.

Here's a bunch of common abstractions.

You've got data structures on the top left; those are your trees, maps, arrays, dictionaries, sets, lists, and so on. They let us structure information in something else than raw bits in memory. That's obviously good.

Then we've got the identifiers. I consider them an abstraction. They can be your auto-incrementing IDs in a database, a UUID or a GUID, but also a variable, a pointer, or a URL or URI. They basically let you refer to a logical entity, piece of data or object, without having to describe it fully. They're usually bound by some context to give them sense. I can say "you're John" and people who know a given John will have a an idea of who John is that is related to the person they know, with things like height, occupation, age, and so on. Identifiers let us have a thing that stands in for the whole true item.

Then we've got numbers. Nobody in here today could raise their hands and say they implement their own half-adder in every project they make. We mostly just use numbers directly and don't go around wrangling bits by hand anymore.

Bottom left, we've got the network. That stuff is just abstractions top to bottom. There are your connections, ordered streams of data, IP addresses and port numbers (which are also identifiers!), packets, and so on. We fortunately don't just handle electric signals down a cable by hand in there.

Then we have time, and here I'm not gonna describe time because it took philosophers, metaphysicians, and scientists millenia of arguing to get to our approximate understanding of today.

Then we have strings, our general "whatever fits" storage for a bunch of stuff we don't know how to represent.

Each of these critical tools we have are essential for us to be able to do work and accomplish tasks without knowing everything from the entire stack and having to know the decades of science, math, and engineering required to build these things. Yet, if we aren't aware of some of the limitations of these abstractions and we use them in ways that clash with their actual properties, they can just straight up bite us in the ass.

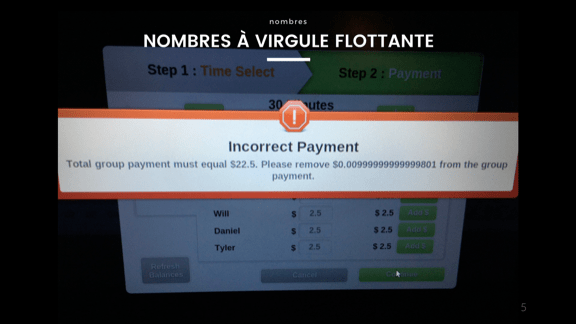

Let's start with an easy one, floating point numbers. If you've seen

0.1 + 0.2 be equal to 0.30000000000000004,

you know what this is. There's an infinity of numbers between 0.1 and

0.2, but we only have a limited number of bytes to represent them. Some

numbers don't divide up exactly, and without working in fractions it's

gonna be very hard not to go and lose precision where the computer

starts fudging the numbers up so they make sense.You may have seen this whenever working with money. The trick is to never use floating point numbers to work with money if you don't want it disappearing. Always use the smallest indivisible unit you'll need and work from there. I don't care if it's cents, millidollars, picodolloars or femtodollars, just don't use floats.

I've heard of a cool project where a bank tried to put a wrapper around their old code base using node.js. Unfortunately for them, nobody told the team about the fact Javascript only has floating point numbers, and they had to scrap the project.

Speaking of which, languages with only floats like javascript have an upper limit on the precision of integers; 2^53 in this case.

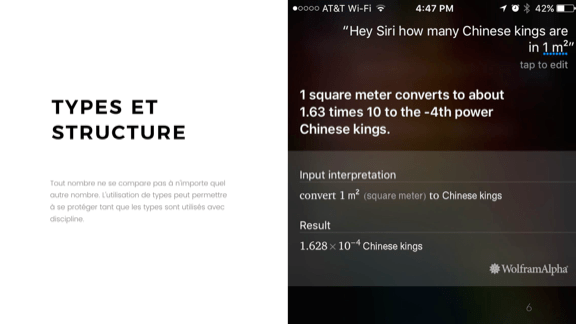

With integers it's a bit easier. For the most part, people know and understand the limitations to a much greater extent and it helps. But that's not enough; you need to have the proper structure and type usage since not all integers stand for the same thing. Just think of the Mars Climate Orbiter, which failed because some bits of code worked in imperial units and others worked in metric. Whoops.

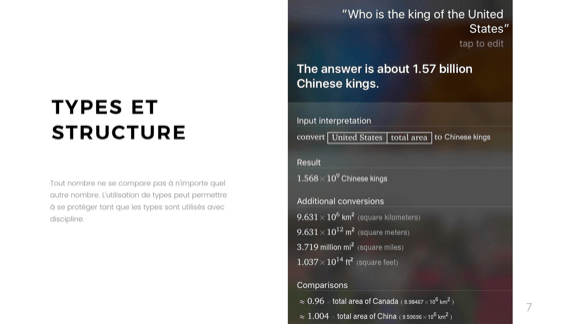

On the image here we get a specific view of these confused units. Ask siri or wolfram alpha how many Chinese kings are in one squared meter and you get 1.628*10^-4. Not quite sure what that means, but it still reliably does it.

It gets even better when you lay on some language processing. I can't figure out why, but "Who is the king of the United States" gets answered with 1.57 billion Chinese kings.

That kind of error is usually fairly simple to prevent. Be careful, and if you have a fancy type system, use it fully. Don't go for 'integer' for all of your types, specify what the integers represent, what their unit is.

So let's say that my application handles its redundancy fine, and then got its numbers game fine also. Maybe I even get users. Now I'll look at fancy things like sharding, or maybe I'll just work with external services. In either cases, I'll likely get UUIDs or GUIDs thrown my way, since they can 'guarantee' uniqueness without being predictable.

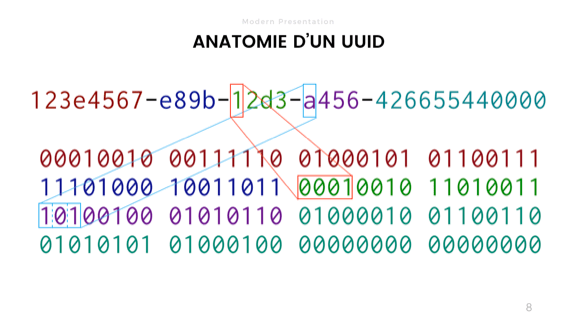

A UUID is just a bunch of bits that you compare. If all are the same, the identifier matches. If not, then it's different. There's a bunch of different varieties, some random, some time or address-based.

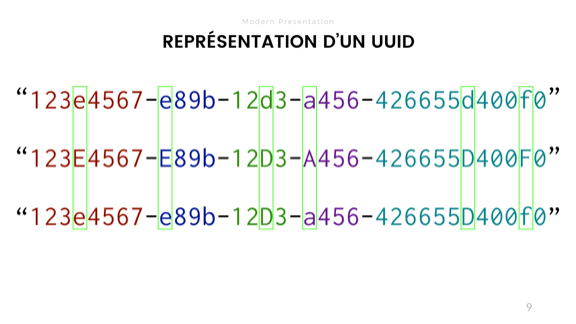

The way we usually see UUIDs though is the one on top of the slide, with hex numbers split by dashes. That's a bit risky.

Depending on the language or stack you use, you may have libraries that let you store UUIDs as binary blobs in memory. Or you may have to use strings to store their abstracted representations. In some case, you have to use strings as an intermediary format, say when transmitting the information over various systems that do not support raw binary data, such as SQL queries or JSON.

There lies the risk. By default, most strings in most languages have comparison operators that are case sensitive. This means that these 3 UUIDs, despite being identical in their authentic binary representation, wouldn't compare as equal as strings. Case insensitivity is warranted and must be explicitly considered by your system because the string representation is not a perfect abstraction of the true properties of the UUID.

In fact, this can cause major headaches if your various components do not all use the same exact representation. Your clients, front-end, back-ends, databases, and cloud services must all either do case insensitivity or agree to a common representation.

For specific languages, specific libraries are required, some which will and some which won't do things right. Databases can be tricky:

- If you use PostgreSQL, you get a case-insensitive comparison, but a lowercase representation.

- MySQL supports generating uppercase UUIDs, but has no storage format for them. A VARCHAR is recommended, which is case sensitive

- MSSQL can store GUIDs, but goes for an uppercase representation

- Oracle can store raw data, so should be okay

- Redis has no support for UUIDs and likely you'll use a case-sensitive string

- MongoDB actually does things right and uses a binary representation.

Any single part of the system not doing it like the rest can cause issues. Then you'll be stuck having to store a canonical UUID (for comparisons) with a string copy of it (for its origin version) or you'll have to figure out and document how each service internally stores stuff. Not fun.

But string comparisons can bring us more problems. Another interesting property of strings being compared (but not just strings, most arrays and data structures also), is that you want the operation to go as fast as possible.

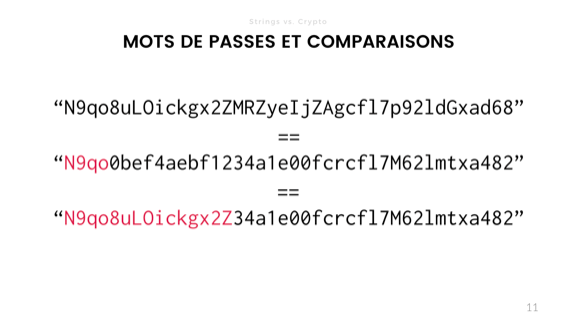

If I'm comparing the following password hashes, with the topmost one being the correct one, and the second and third ones being other attempts, the moment my '==' operator hits a difference, it bails out and returns 'false'.

Now that's interesting because the duration of the computation is information. In security and cryptography, we want to hide as much information as possible. What an attacker could do then is send many, many requests with various guesses, and then see, based on how long it takes, how close the guess is to the solution. This can leak information about the hash value and inform further guesses in time.

That's essentially what a time-based attack is, although there's more types of it than just that.

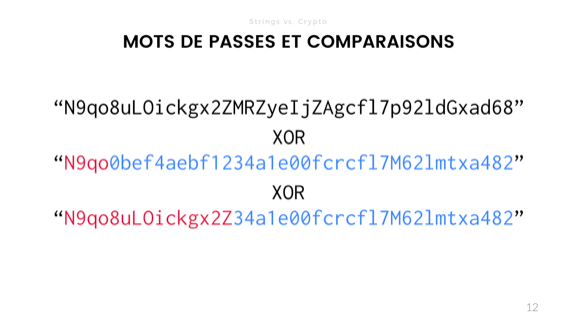

The way around this is to replace our comparison operator with an exclusive OR. Set a value to false, and then compare bit by bit or byte by byte with the XOR. Every time both values are the same, it returns a 0 (false) and every time the values are different it returns a 1 (true). OR that result into the initial value and if it's not 0 at the end, you know there's a difference.

You still have to be careful to ensure that you don't leak information about the length of data or that specific optimizations don't hurt you. Good cryptographic libraries do this for you anyway. Use bcrypt or scrypt and you should be fine for passwords, but the more you know the better.

It's one of the funny things of cryptography that sometimes you want things to be as slow as possible in terms of design, but as fast as possible in the implementation, since that prevents brute force attacks

Of course some organizations take this a bit too much to heart and their slowness is not really mandated!

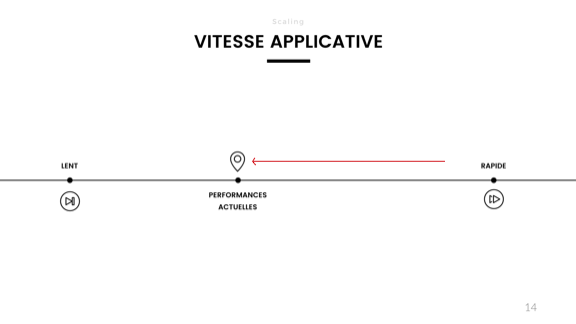

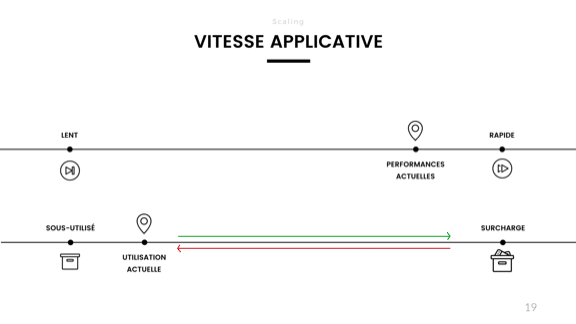

So we've got that fancy application, it now handles redundancy, integers, floats, UUIDs, and passwords fine. I'm getting a lot more users, and performance starts to degrade when I measure the response time. I've read these blog posts that tell me that I lose an important percentage of my users with each tenth of a second spent not responding, and it's time to react!

Some operations take longer and stall the rest, and generally it's just really hard to predict things, and peak times are annoying. Someone on the team comes with an idea that would solve all problems. What is it?

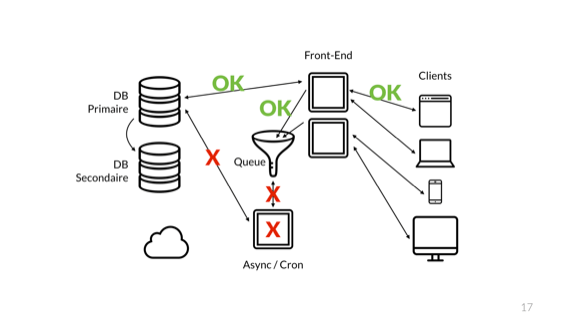

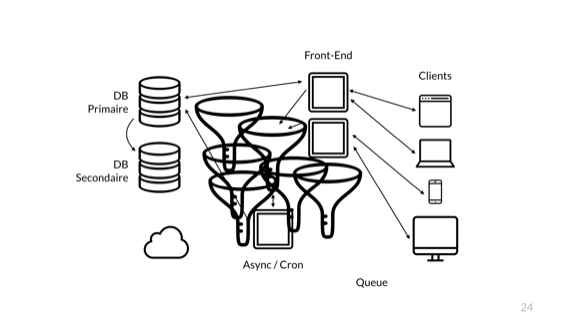

Stick a queue in it! The front-end server just sends its short easy requests to the DB directly, and all the complex ones that take time are sent to the queue. The queue accepts without processing and I can quickly return the results to my users.

And suddenly, all my performance is back. Hell, it's even faster than before!

There's a problem looming, though.

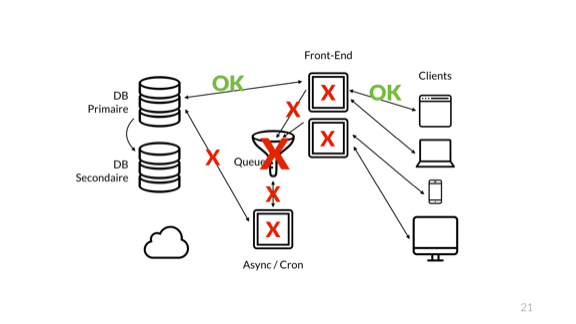

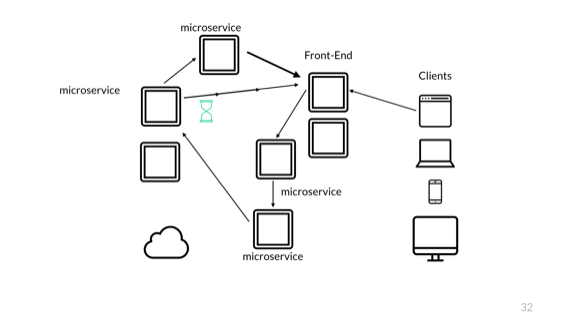

When we added a queue, the interesting thing that happened is that I stopped conveying the overall health of the system to the front-end. Whereas earlier the users of my system could see whether their requests entirety worked by virtue of returning the result of the end-to-end operation, the usage of a queue broke this concept.

Right now, the front-end only lets us know whether its direct connections are healthy. We have no clue regarding the consumer of the queue, about the async server, or the async server's ability to talk to the database or the async queue itself.

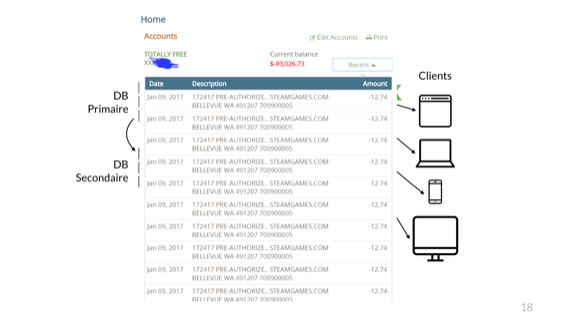

In fact, if work is not done carefully, events can repeat itself. Here's a reddit user who bought a $12.74 game and got charged for it so many times despite buying it only once his bank account got overdraft to -$93k.

There's no clear guarantee the issue here is specifically caused by a queue, but I've personally seen many that looked just like that in these situations. When things go wrong and the end-to-end flow of data gets to break up in mysterious ways, the effects are usually very noticeable.

But there's more. The reason my application initially got slow was because it was being overloaded. Right now though, I have entirely disjointed the perceived performance from the actual load in the system.

No matter how bad things get in the back-end, the front-end performance does not budge. This was good in the case of temporary overload for some large operations, but is pretty bad when it comes to long-term stability. By monitoring front-end performance we inherently had the pulse of the whole system. By splitting up the system in two parts, my front-end monitoring not only shows the health, but also the performance of half the system.

And eventually, the queue overflows and crashes. Of course it does not crash alone

The error then blows up to the front-end nodes and we cascade to a full catastrophic failures.

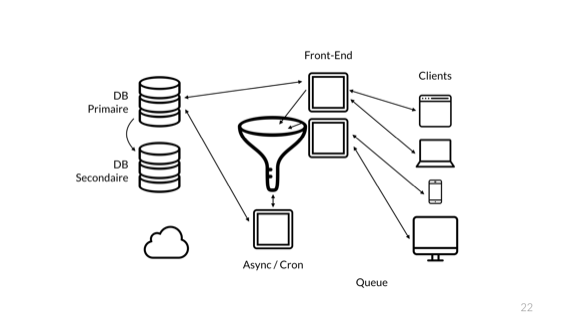

So what do we do? Someone calls a meeting, says it is unacceptable for this to happen. So what do developers do?

Make it a bigger queue. But there's more. Since during the crash all the data in flight in the queue was lost, everyone also agrees to make it a persistent queue. That slows it down, and since we love redundancy, why not add another one?

And the next time the error happens, we can do the same again.

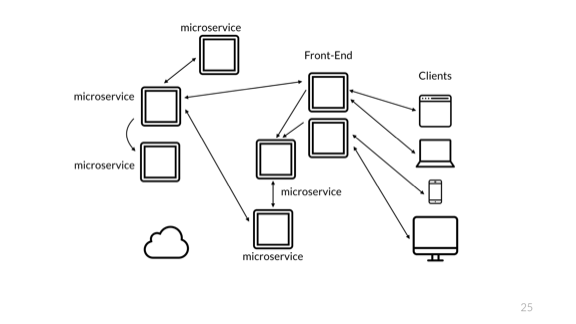

All those queues are pretty good. But we're a cool and good company and so we want next gen tech. We all know this architecture diagram is terrible. So we do the proper thing...

Aww yiss, microservices!

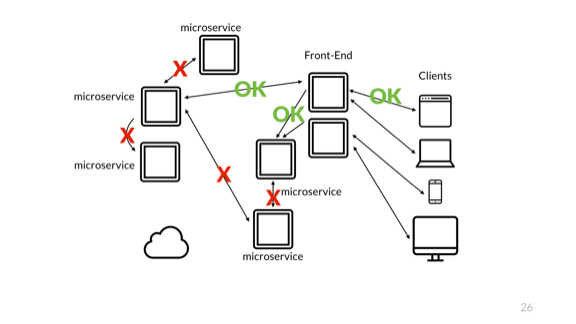

Of course the problem is exactly the same. The big issue still has to do with the monitoring of only a partial system. Changes in architecture like that should be seamless to users, but have very important impacts to the team maintaining and operating the system.

Conflating the user and the operator, or omitting either of them is a killer mistake for your project, and for them. Operations get very tricky.

Of course that's not all! All our components have to be able to talk to each other.

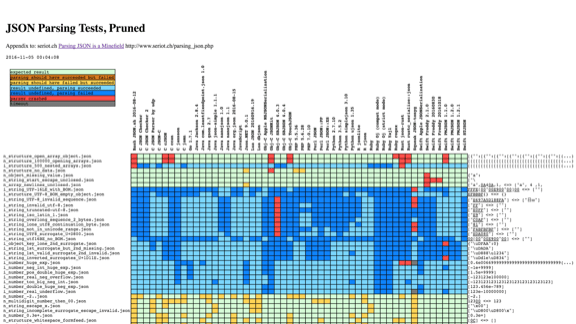

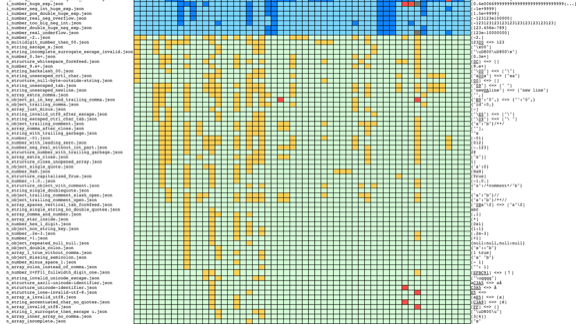

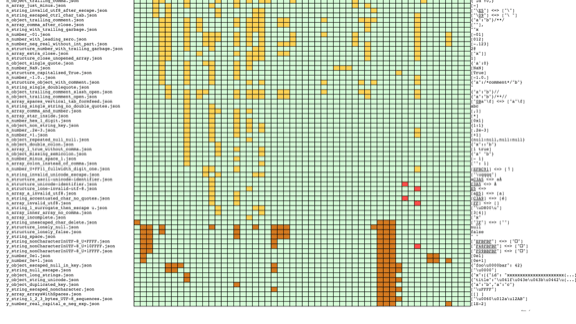

We could pick something like JSON. This is a chart from seriot.ch, observing about 50 implementations of JSON libraries across more than 10 different languages.

Almost every one of them handles some things differently.

That's not great

The JSON standard is very small, but this likely means it gives a lot of place to interpretation, and therefore to special unorthodox behaviour.

The fun bit is that if you run many microservices and send the same carefully crafted data set to all of them, you can generate confusing behaviours. Take for example the case of an invalid JSON map that contains the same key multiple times, with different values. Say I have an object 'person' where the 'name' attribute appears twice, once with the name 'Mark' and once with the name 'John'.

It's entirely possible that any parser behaves in one of three ways:

- refuse to parse the record, as it should

- keep the first name (Mark)

- keep the second name (John)

If I have 3 services each having their own version of each behaviour, I have one service that will stall and crash and refuse to handle the record, and then two different services that see different values for the same object. Handle with care.

Another problem has to do with time. Different clocks go at different speeds. I made the experiment last year for a presentation on calendars (no, don't laugh, calendars are actually super interesting), where I disabled clock synchronization on my computer.

I then checked it against my oven and my microwave oven to see which would drift the most. After about 3 or 4 weeks, the microwave oven had about 3 minutes of drift. My laptop itself had drifted roughly 2 minutes and 16 seconds. The oven, for its own, had remained pretty much on time.

Clocks change based on hardware, temperature, voltage, humidity, and so on. They just can't be trusted to be accurate over longer periods of time.

This means that without synchronization, a set of timestamps for the same event can all become disjoint and give very odd results. So you want to be using NTP and keeping an eye on it to make sure it doesn't drift too much. Even then, for very rapid events, NTP can have enough variation to cause issues.

And that can even happen on a single machine. At a previous job, we once crashed a hadoop cluster. What happened was that we would run quick bids on the millisecond scale, and would take time stamps at two points: when receiving the request and when finishing the bid. We could then use either to log the event and could calculate the time difference to know how long the whole processing took.

On a fateful day, on a transaction that ran particularly fast, the NTP synchronization of the computer clock drifted it back by a few parts of a second, just enough to apparently allow the second timestamp to give a time prior to the first one. To make it better, this turned out to happen at around midnight on the last day of a month or some other log rotation.

The events ended up finishing on the day before the one it started, and very much confused the cluster, which just bailed out on the apparently garbage data.

The trick here is to make a strong distinction between monotonic and system time.

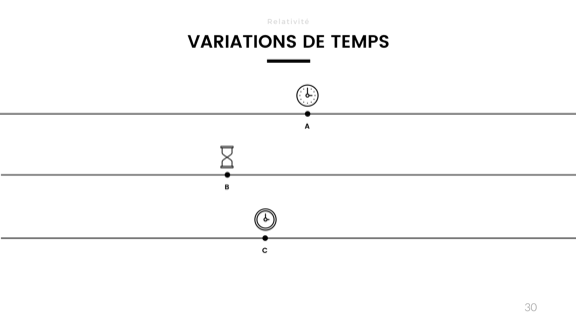

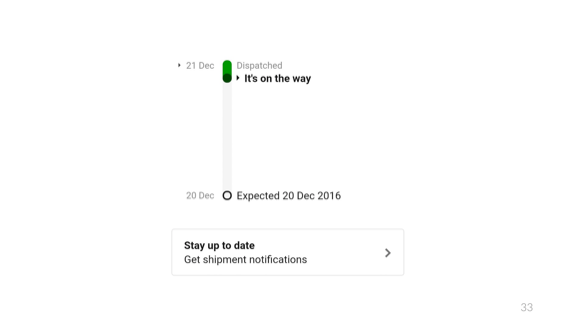

Oh but there's more. Time is always bad news. When we work with systems like that, we may get entirely different logical endings.

Here in this case, the customer may send a request, which makes it to the first service, then to a second one, and then to a third one. Let's say this service confirms that an item was bought. It sends a notification of this to the front-end.

After having sent that notification, the service instantly sends the order to a fourth service, which sets up say, a confirmation of shipping or something of that kind. That fourth service also sends a notification to the front-end.

What can happen here, through the magic of network delays, is that the front-end is made aware that shipping is taking place before the purchase is even confirmed.

This is tricky because you have, if you're the front-end developer that is, to be aware and able to foresee these things and deal with them properly. If the same events go to some audit system instead, it could very well consider it a bug, ring an alarm, cancel the shipment, and so on. Who knows what horrors may happen.

The need for this then is to consider logical time to track causality, rather than having it implicit, but that's too big to cover here.

But these kinds of logical errors are fun, and can let us do time travel.

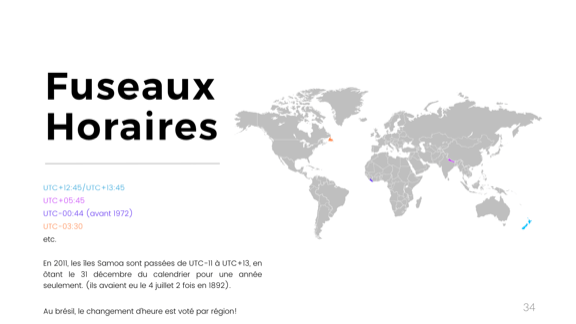

But that's not the end of it with time. People here are generally aware of time zones. But who here is aware of the time zones on the half hour?

(most people raise their hands)

That's good, since Newfoundland has exactly that. That's within the country so it's good that you know.

But then again, who's aware that we have them on the quarter hour? New Zealand's got that. Or that Liberia once had it on the 44th minute of the hour? Maybe some here are aware that in 1927, China went back 5 minutes and a few seconds on their time zones!

But there's more. Changes in time zones aren't always minor. The Samoa Islands, for example, switched back and forth between UTC-11 and UTC+13, switching days entirely. The trick is that they're on the date change line. In 1892, the Samoa Islands decided to align their calendars with the US for market reasons, and had the 4th of July twice that year. First of July, second of July, third of July, fourth of July, fourth of July, fifth of July, ...

Then again in 2011 (that's not that long ago!) they aligned with China, and in the Samoa islands only, there was no December 31 that year.

Then there's daylight saving times. If you know Brazillian sysadmins, you may have heard of that fun fact that (and I don't know if they still do that) each region/province/state in Brazil would vote whether they would adhere to DST every year, every time. No way to know ahead of time, but you had to update them time zone files.

Then you've got leap seconds. With time zone issues, the trick is often to just use UTC. But this has nice effects since everyone kind of still uses unix timestamps underneath and freely converts between UTC and the epoch starting at Jan 1st 1970.

That's because UTC accounts for leap seconds, which are frequent adjustments added or removed based on earth's orbit and rotation to keep the clocks in sync with the real world. Since 1970, we're at a net 27 seconds offset. The unix epoch on our systems does not account for them.

The image right here on the slide is from a bug in the iPhone a couple of years ago, where if you would rewind the date on the phone to January 1st 1970, you would brick your phone. It would see all software as invalid and refuse to recognize anything. Fully bricked, no way to repair or reset.

My personal guess as to why this happened (and I very much wish I'm right) has to do with this discrepancy in time representations. If you use an unsigned integer—those pesky integers again—and use them to represent the time starting at Jan 1st 1970 as an epoch, but use a UTC conversion to set the date and time, you end up at -27, which is not representable as an unsigned integer, and we instead underflow. This gives us the year 2106 over 32 bits, which may be too late for any software validation and things just break.

But there's more. Oh so much more. Here in Quebec and North America we use the Gregorian time. Who here has made mistakes related to leap years in their code? (a bunch of people raise their hands)

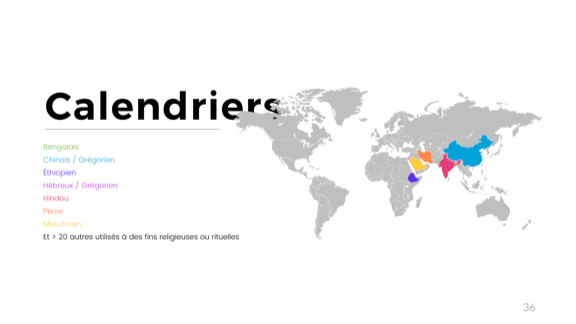

This is not much. There's a lot of calendars in use out there, on a legal status. Even more for purely cultural uses:

- there's the Bengali calendar, which is solar and based on 6 seasons of two months;

- the Chinese calendar, which is a fairly confusing lunisolar calendar, used legally along with the Gregorian calendar in China. That's over a billion people right there

- the Ethiopian calendar which is pretty cool and indirectly derives from the old Egyptian calendar, the first solar calendar we have on file. Its leap days are technically not part of any month. What's neater is that in Ethiopia, their midnight starts at what is 6AM in neighbouring countries. Since Ethiopia has made it a point of pride that they have never been colonized, they are generally not interested in adopting other systems.

- The Hebrew calendar is one of the oldest calendars on file, is both lunar and solar, and has some of the most complex rules I've seen related to choice of dates. Just picking the first day of the year has what is probably a few full pages of business rules. It's usable legally in Israel, with the same status as the Gregorian calendar.

- There's a Hindu calendar, also very complex to me, using both solar and lunar cycles. What's fun is that depending on the region, the new moon or the full moon is used as a cycle beginning so the same calendar gives two varying sets of dates within the same country. But with India in the mix, we're close to a third of the world population pretty frequently dealing with non-Gregorian calendars

- Then there's a Persian one, whose details I don't really remember all that well at the moment

- And there's the Islamic calendar, which is still use in Saudi Arabia for official purposes, but also in other countries for cultural or religious purposes. What's interesting about it is that it's an observational calendar, meaning that every new lunar cycle, some authority figure has to get out, look at the moon, and say "this is a new moon, we officially have a new month". In the past, when more countries used it, it was possible to get a bunch of months starting on different dates for people all using the same calendars, since observations would vary according to locations.

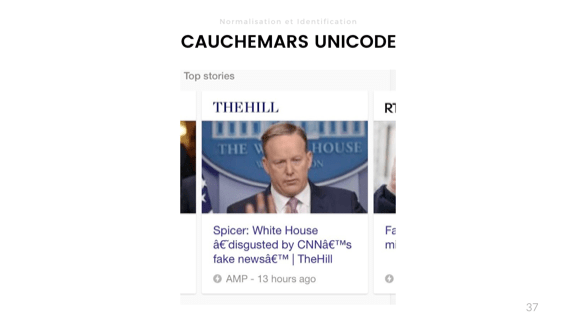

Oh no. Unicode. I assume a lot of people here have had their own names mangled by various systems given all the French accents. Show of hands? (over half the room raise their hands)

Yeah. So you know how that goes. The problem for that one is a conflict in encoding between Latin-1 (or ISO-8859-1) and UTF-8.

The gotcha here is that in the lower characters, UTF-8 and ISO-8859-1 are absolutely the same, with the lowest characters shared with ASCII.

So we have to configure every step of the way to have the same encoding. This starts at the client, but then the data transfer with HTTP (including the pesky meta tags), the instances themselves if anything comes from there, then the programming languages used (some functions are not inherently UTF-8 everywhere), then the connection to the database (since SQL is text-based, it is encoding-sensitive), and then the database itself. If you're lucky, your DB also lets you set a configuration per table, and per-column.

Any of them being wrong and it becomes impossible to figure out what went wrong; you flat out corrupted your data and human intervention will be required to make sense out of it.

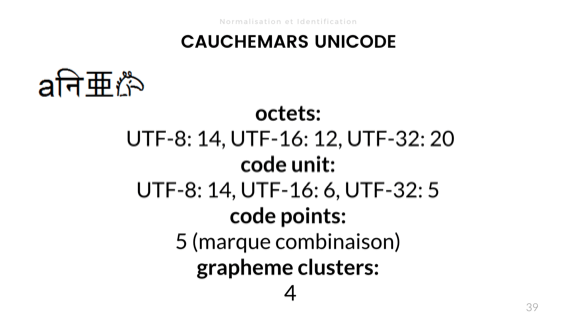

Length is also variable in Unicode. There' 4 ways to account for it. Using that funky little string with the 'a' and the horse in it:

- There's byte length, which gives us 14 bytes in UTF-8, 12 in UTF-16, and 20 bytes in UTF-32

- There's a length in code unit, which is about how many bit combinations are used for each encoding for the string, here being 14, 6, and 5 in this case, for UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32 respectively

- There's the code point length, which is based on the number of logical Unicode 'characters'. Here the length is 5 since the second character here is made with a combining mark giving it its cool little curve on top.

- Then there's grapheme clusters, which are what we humans consider to be characters. I like to describe that one as "how many times you need to press the delete key until the string is empty". That's a length of 4.

That one is fun. At a previous job, we once took down an entire cluster for 40+ minutes as a binary protocol mandated byte length over the data it shuttled, but one of the two ends of the communication used code point length to work. This went fine for years, until we started transmitting arbitrary data carried by customers. It took about 30 seconds for someone to put in data with Unicode that desynchronized both protocols and took the whole thing down.

We rolled back ASAP, but it took us about 3 days of investigating to figure it out fully. Good time to be on vacation.

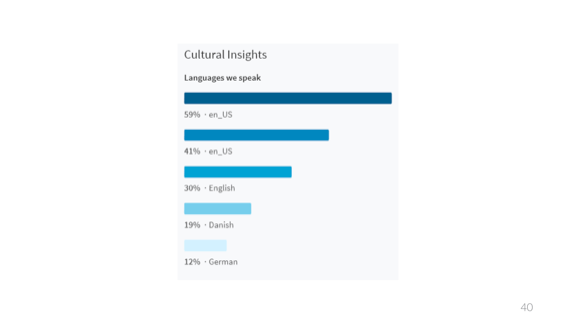

That one is a poll about languages used. Not sure how they got these results, but it seems about right to me.

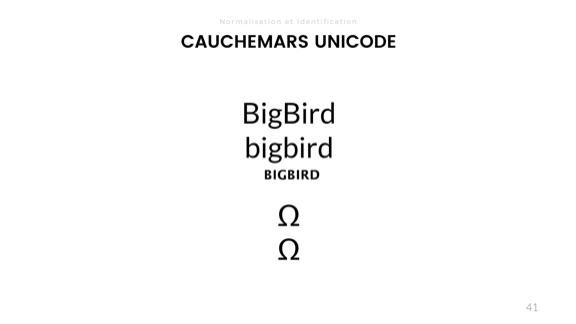

Ah that one is fun. I got this one from some fun bug Spotify had a few years ago, so instead of recounting the words I said in a talk, I'll link directly to their blog post: https://labs.spotify.com/2013/06/18/creative-usernames/

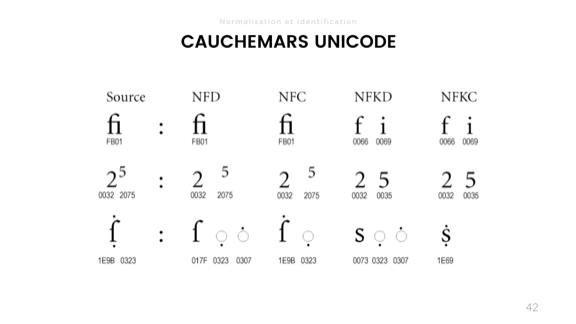

This slide explains normalization of Unicode. It was used as a support for the Unicode bug at Spotify, so here's the link to the blog post again: https://labs.spotify.com/2013/06/18/creative-usernames/

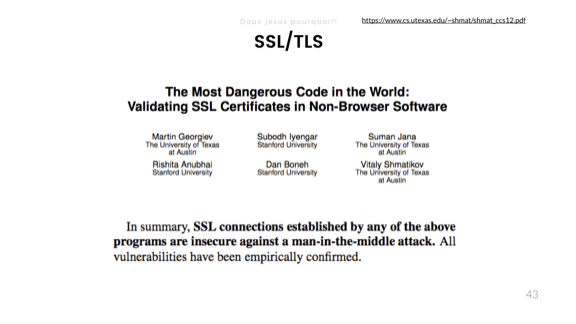

And now we get to the real fun stuff! Security! This is from a 2012 paper called The most dangerous code in the world: validating SSL certificates in non-browser software which I encourage you to read.

When it comes to bad abstractions, security takes the cake. What they found is that pretty much all the software they looked at that had to validate certificates, outside of web browsers, would do it wrong in critical ways that would allow Man-in-the-middle attacks, where someone can intercept, peek at, modify, or hijack the entire session. Fun times.

Here's a good snippet from the OpenSSL library, with such a bad interface a bunch of people missed critical bits of validation.

And here's one about GnuTLS, with a "similarly atrocious" interface.

But my favorite has to be the cURL API in PHP. By default, settings are fine and correct, but if you read the doc, you may want to set the

CURLOPT_SSL_VERIFYHOST option to true. The problem is that in PHP (much as in C and C++), true is pretty much the same as 1. Yet, the value 1 for CURLOPT_SSL_VERIFYHOST actually disables validation. The correct value is 2.Whoops.

This brings me to the concept of class breaks, which I've first heard described by Bruce Schneier on his blog.

The idea is that a lot of real world physical systems are weak and easy to break. The locks on our doors are like that. There's multiple ways to lockpick or bump your way into a home, but every attack has to be repeated independently.

In the case of software, you have the concept of a class break, where the moment you find a vulnerability, there is potential for it to be used to exploit everyone at once. This is relatively new and particularly scary.

The Internet of Things, hailed as fairly amazing in this here conference, is particularly worrisome. Implementations are just bad. the more code you work on, the less you trust IoT developers are doing a good job.

There's been fun examples, ranging from hacking cars and driving them into ditches (was that dongle your insurance company wants you to use to lower your premiums something car constructors were ready to connect over a network?), fridges sending spam, devices getting involved into botnets that take infrastructure down, and so on.

So that's where it leads us. We had what was seemingly a very straightforward application, but riddled with potential bugs we have nearly no way to guess could even exist. Yet these sharp edges are embedded at every level of the system. As a developer, what's our responsibility? Do we have to answer for things we don't even imagine could be there?

The building code was put in place probably because too many people were being crushed by their houses collapsing on them. Relatively few people have died from bad code at this point in time, but software sure is eating the world. The code we write makes it out there and can stay for very long periods of time, far longer than we'd all hope it lasts every time we add in some quick fix.

Do we take adequate means to make sure what we publish is safe? Are we allowed to freewheel the way we do just because we haven't killed enough people yet? Are we collectively aware of the problem but just shedding our personal responsibility until something big forces us as a whole to do better?

I don't know for sure, but all of that stuff is very scary, and I just hope I'm not one of those that will end up causing enough grief to require laws to be put in place. Maybe all of us should fear that a bit. Everything's terrible, and we've got a part of blame in this.

Brak komentarzy:

Prześlij komentarz